Sometimes, I think the only way to solve the VAR problem is to implement yet another video replay system which reviews the decision-making process in the video assistants’ nerve centre – Stockley Park in the Premier League’s case. Lines drawn from eyes to screens, computer monitors checked and rechecked for resolution problems, every minutia of the office environment analysed with neurotic attention to detail – it’s a jobsworth’s wet dream. Thousands of hours of VAR, each more climactic than the last. Constant, dizzying, 24-hour, yearlong, endless VAR. Let’s see how they like it.

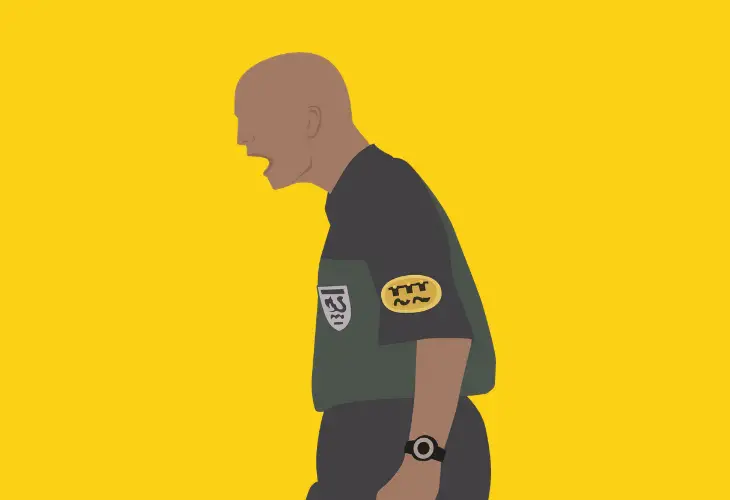

I’m being facetious, pedantic, bitter (take your pick), of course. But it’s hard not to feel some bubbling resentment when you see yet another otherwise superb goal ruled out for offside because the forward forgot to shave their knees that morning. As this live-action nit-picking unfolds, the referee stands there lamely. He holds his earpiece apologetically, his body language grumbling, his agency stripped, his once-highflying status reduced to that of a glorified baby sitter. He’ll break up the occasional squabble, pick up the occasional spat-out dummy. But ultimately, he won’t affect the action beyond carrying out the admin.

It makes you long for the days when you would see Pierluigi Colina, slinking, lynx-like about the field, bursting with an almost volatile authority. It makes you look back fondly at the Howard Webb-Manchester United nutjob Twitter conspiracy theories, because back then it actually mattered who was refereeing a game of football.

He was wearing a different colour, but it felt like the referee was a player in the game, not just a passive onlooker. Football is a game of so many moving parts, and the referee was an important cog in the mechanism. For now, they still have control over the flow of a game, the little fouls they let go, the timing of the bookings and so on. But for how much longer? The trend is moving rapidly in the other direction.

Football is becoming uniformly meeker, more homogenised, less character-based. In what seems to the layman like a baffling equation, the stakes are going up while the commitment is ostensibly going down. As this curve continues, what happens in the middle of the pitch – now the referee’s sole zone of influence – becomes, in officiating terms, less and less important. What used to be a battleground is now a chessboard, and you’re unlikely to see a knight perform a crunching slide tackle on a pawn.

With referees stripped of the ability to make big decisions, one of the oldest dynamics in football has eroded. There was a pantomime beauty in thousands of fans going ballistic at the man with the whistle. I suspect most of the officials got a perverse enjoyment from it too. You don’t get to the apex of the officiating game without deriving at least some enjoyment from being the villain of the piece. It was in their nature to be contrarian. They grew up as football fans, and while they might never have had the chance to make it as payers, they were still one of the stars of the show. Now the character of the ref is largely inconsequential, and they’re less the star of the show and more the antagonist in a political slugfest.

There’s an argument to say that the banal, overzealous attitude towards the application of the Laws of the Game implicit in VAR is morally right. And yes, maybe if we’re speaking in the purest Kantian terms, that’s probably true. But it is a game of football, not a cosmic ethical playground – ultimately, it doesn’t really matter. Why not sacrifice an iota of fairness for an ocean of amusement.

I for one would take the occasional dodgy refereeing decision going against my team. It was a worthwhile trade-off for all the enjoyment I got from watching the drama unfold in other matches. And for every dubious call, there was an opposition team benefiting from it. That’s Newton Third Law of officiating. Every action on the pitch has an equal and opposite reaction somewhere in the stands.

But thanks to the advent of technology in football, this has become a pointless debate. It’s unlikely to go away any time soon. In fact, it seems likely that the robots will encroach even further into the game. Football is a goliath business, and investors will always look to reduce the role chance can play in their interests. As the game moves further and further towards hypercapitalism, the referee’s zone of influence will shrink. In the future, the referee will probably only remain on the pitch as a ceremonial gesture.

In a way, that’s the state of play already. The Premier League is a uniquely multicultural industry. It belongs, not to England, but to the world. Hundreds of nationalities are represented throughout its sporting and regulatory echelons. Whether this is a good thing is a bone of contention for many English supporters. On the one hand, the quality of play is increased, there is more tactical diversity, and the sport can be used as a vehicle for societal change and tolerance. On the other, it harms the national team’s chances and – arguably – means that fans identify with the action on the pitch less and less.

But while Mike Dean is still peacocking about the pitch, handing out more cards than Clintons, there is at least an English undercurrent. The many pundits and commentators who have an almost militant opposition to fun in any form, who lambast Dean for daring to impose his personality on the game, they ought to remember he is doubly important. He’s a home-grown ambassador for the English game, and he is doing something to restore the centrality of the referee and rediscover the lost art of refereeing.